Before I continue my mini-series

on colonial myths, I’d like to offer an overview of the Southern Campaign of

the American Revolution. How many know what that refers to? Unless you’re a

serious American Revolution buff, chances are you don’t.

|

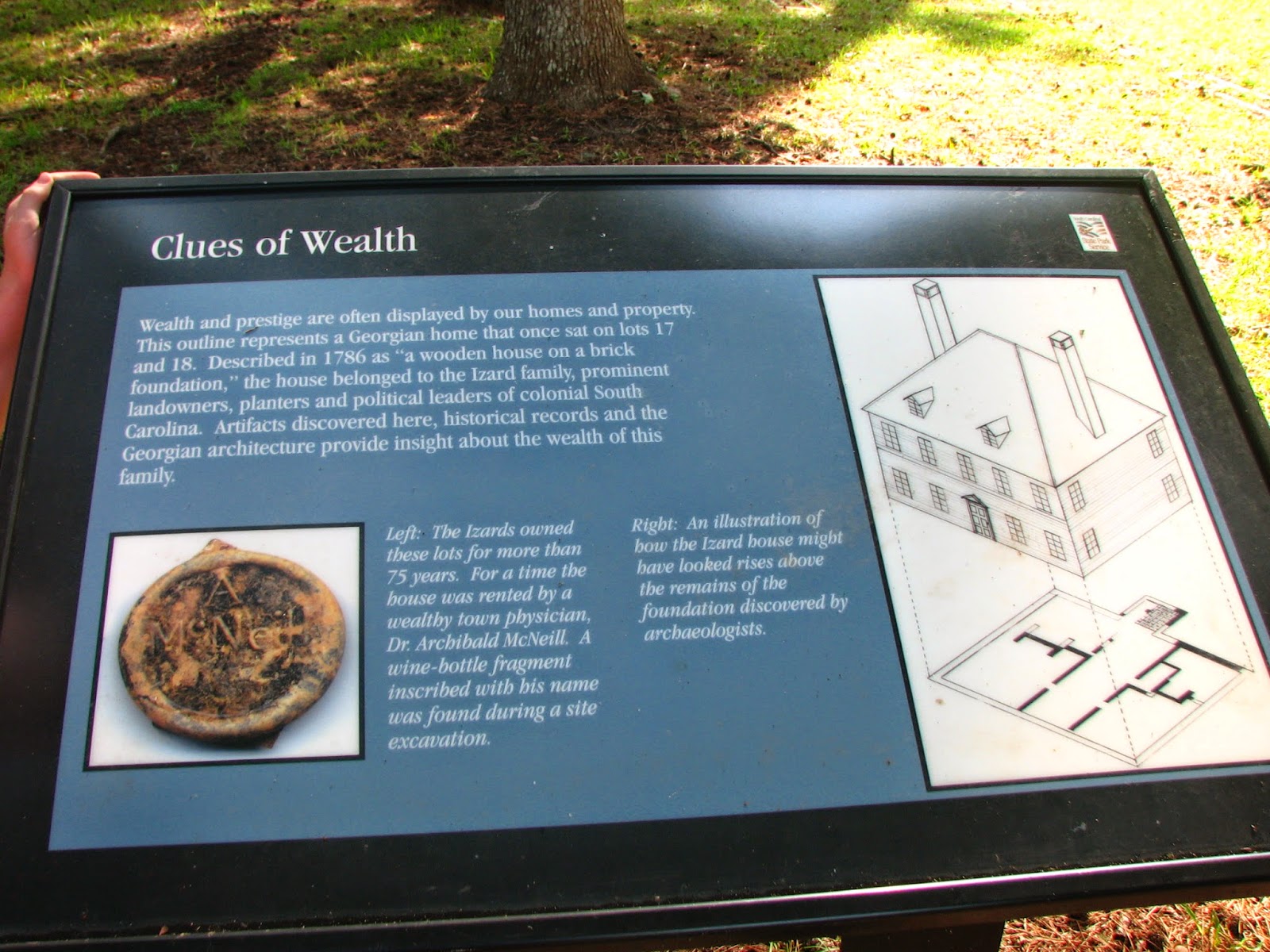

| Kershaw-Cornwallis house, Camden, SC, British headquarters 1780-81 |

The

history taught in schools is sketchy at best, and sometimes

riddled with myth. Where the Revolution is

concerned, we’re familiar with the Boston Massacre, Lexington and Concord, the

Declaration of Independence, Valley Forge, and Yorktown. What happened in

between is fuzzy at best, or missing completely.

We also know

individual legends like George Washington and the cherry tree, Betsy Ross, and

Molly Pitcher. We’ve also heard of Benedict Arnold’s treachery, and we know the

difference between Whig and Tory.

The average

person is willing to let their knowledge of history be informed solely by

grade-school textbooks, or films like

The

Patriot. Those of us who have an interest in blogs like this one, on the

other hand, thirst to know more ... to get the facts right. :-)

I shared

already how

a common reenactor myth sparked a story idea, then sent me in

search of solid provenance for said story.

As I got deeper into the research, it took my

breath away at how little I knew of the Revolution as a whole.

Like the fact

that the whole second half of the war took place in the southern colonies.

|

| Siege of Charleston display at the Charleston Museum |

The war had

gone as far as it could in the northern colonies—the British held New York,

Boston, and Philadelphia, the major cities. The British cast their eye to the

South—for the second time, since an attempt at taking Charleston had failed in

1776. (Much is made of that in Charleston colonial history, in fact, with

barely a mention of later events.) This time the effort began with Savannah,

Georgia, a lesser port than Charleston, but also an easier target. Savannah

fell to the British in late 1779, and the British then turned their sights on Charleston,

arguably the most important port and the richest city in the colonies. With a

combined offensive on land and sea, the British caught Charleston in a pinch

and held it under siege for nearly two long months, March-May 1780.

When the city

fell, May 12, 1780, Lord Earl Cornwallis was left to implement the next stage of the "Southern strategy": push

into the backcountry while holding Savannah and Charleston. A good part of the populace was believed to be loyalist,

but not as many as the British counted on. Their initial plan to establish a

network of outposts went smoothly enough at first, but then trouble flared in

the backcountry of South Carolina in particular, around Camden, with what

became known as the Presbyterian Rebellion. (The trouble was chiefly among the

Scotch-Irish Protestant population.)

General

Washington sent a force southward, headed by Horatio Gates, and in August 1780 the

two armies met just north of Camden, in the wee hours of a moonlit night.

Fighting broke out at dawn, and a hot battle turned into a complete rout of the

Continental forces, many of them unseasoned militia. Gates was summarily fired

after having fled ahead of his troops, and Continental commissary officer

Nathanael Greene, a former Quaker, was assigned the task of regrouping the

Continental forces and finding ways of making the militia function under fire.

Greene, it

turned out, had a genius for logistics—literally, wearing out the British army.

Rather than win the war by military might, or number of battles won, he

employed a strategy of cutting off supply lines and making it untenable for the

British to hold their various outposts.

|

| The force that turned the tide of a war ... |

The patriot

militia and Continentals won a few of their battles, notably Kings Mountain in

October 1780 (a huge surprise, for being mostly Overmountain men untrained in

battle) and Cowpens in January 1781 (where Greene found a way to persuade the

militia to stand in the face of fire). Others weren’t a dead loss but also not a

clear-cut victory on either side, such as Hobkirk Hill in May 1780 (the second

battle at Camden)

and Eutaw Springs in

September 1781. Some were a nightmarish, bloody ordeal on both sides, like Guilford

Courthouse in March 1781. Cornwallis reached too far and subjected

himself and his troops to an awful, bloody race through North Carolina in the

spring of 1781, which after Guilford Courthouse led to the British army limping

off to Wilmington, North Carolina, until a fresh press northward to Yorktown, Virginia. By the time

October 1781 rolled around, all British troops had withdrawn from South

Carolina outposts and were holed up in Charleston. The British cause in the

colonies was pretty well finished, and Cornwallis had little choice at Yorktown

but to surrender.

These two years

comprised possibly the bloodiest and most brutal of the war. Greene is quoted

as saying,

“Nothing

but blood and slaughter has prevailed among the Whigs and Tories, and

their inveteracy against each other must, if it continues, depopulate

this part of the country.” The Southern Campaign is, I believe, what earned the Revolution the nickname of America’s first civil war. Not much calm and reason here, but passion and fury

and vengeance, neighbor against neighbor and brother against brother.

Links of interest:

North Carolina Digital History's

War in the South

Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution

All photos mine.

.jpg)