Welcome to this month's edition! Just one more month to go and then I'll be on to other interesting things ...

1 - Charles II of Spain dies and is succeeded by Philip V, kicking

off the War of Spanish Succession. (1700)

1 - Mission San Juan Capistrano founded in California. (1776)

2 - Peter I proclaimed Emperor of all Russia. (1721)

|

| Daniel Boone at age 84 |

2 - Birth of Daniel Boone (1734-1820) in Berks County, Pennsylvania.

2 – Birth of James K. Polk (1795-1849), 11th U.S. President,

in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. After serving from March 4, 1845 to

March 3, 1849, he “declined to be a candidate for a second term, saying he was ‘exceedingly

relieved’ at the completion of his presidency.”

3 - King Henry VIII is made Supreme Head over the Church of

England. (1534)

5 - Guy Fawkes Day in Britain: the anniversary of the failed "Gunpowder

Plot" to blow up the Houses of Parliament and King James I in 1605.

5 - First issue of the New York Weekly Journal published by American

printer and journalist John Peter Zenger. (1733)

8 - Cortes captures Aztec emperor Montezuma and thus

conquers Mexico. (1519)

8 - Birth of astronomer and mathematician Edmund Halley

(1656-1742) in London, who “sighted the Great Comet of 1682 (now named Halley's

Comet) and foretold its reappearance in 1758. Halley's Comet appears once each

generation with the average time between appearances being 76 years. It is

expected to be visible again in 2061.”

10 - The U.S. Marine Corps is born in 1775! Established as

part of the U.S. Navy, it became a separate unit on July 11, 1789.

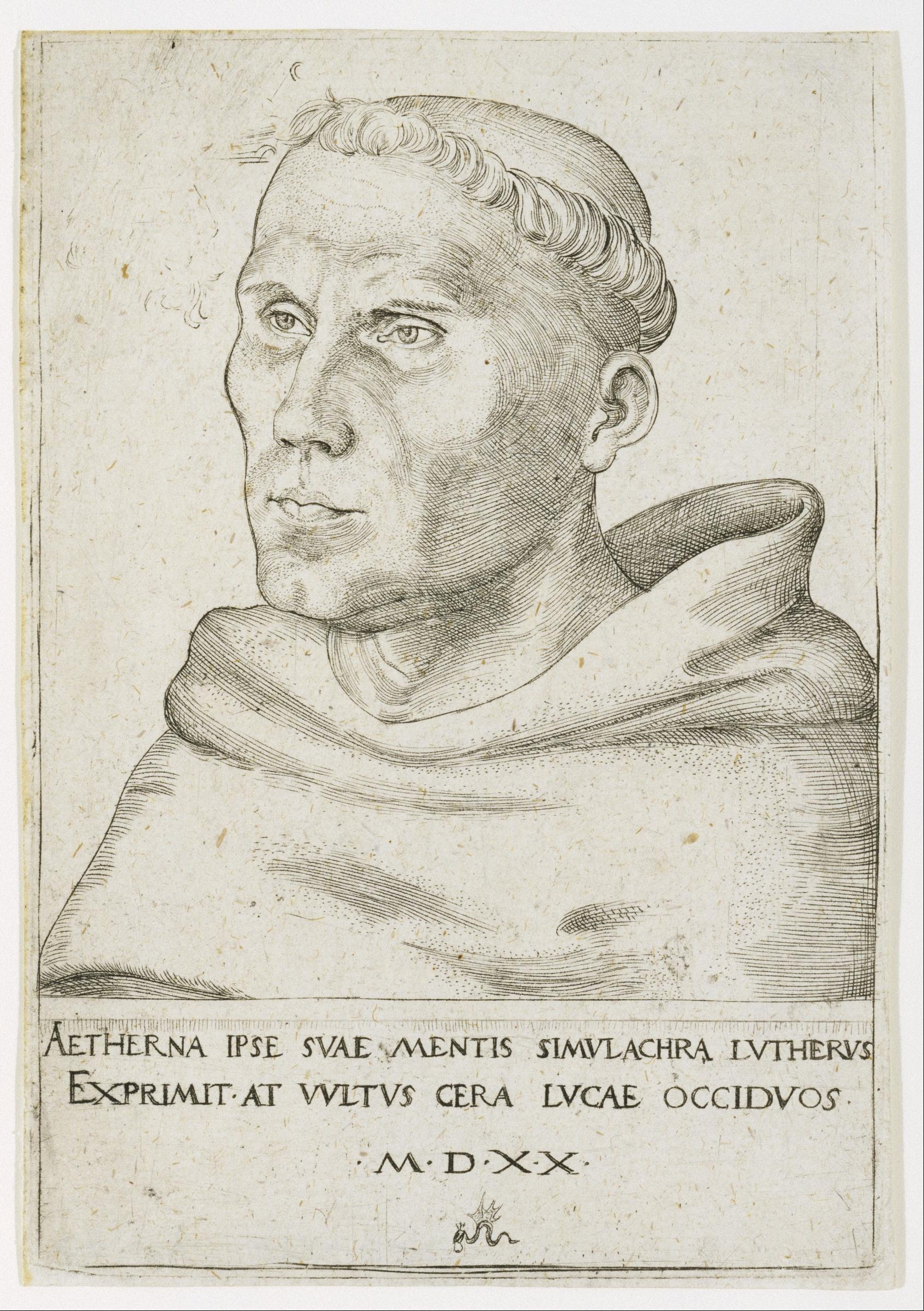

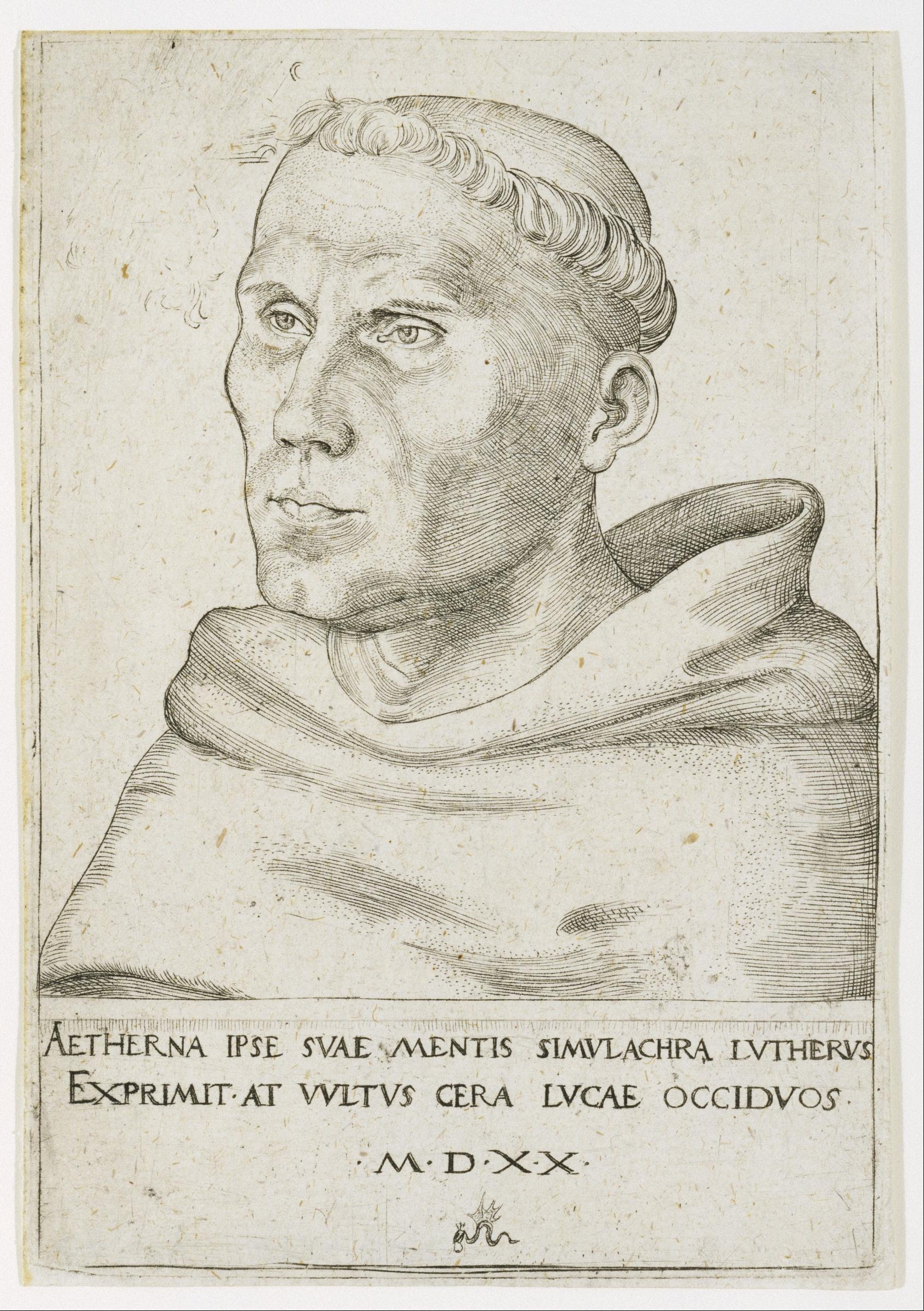

10 – Birth of Martin Luther (1483-1546) in Eisleben, Saxony.

11 - Birth of Abigail Adams (1744-1818) in Weymouth,

Massachusetts.

11 – The signing of the Mayflower Compact by 41 Pilgrims,

onboard the Mayflower, just off the Massachusetts coast. (1620)

14 - The first experimental blood transfusion takes place in

Britain, utilizing two dogs. (...winning the weird science of the month award!)

(1666)

14 - Scottish explorer James Bruce discovers the source of

the Blue Nile on Lake Tana in northwest Ethiopia. (1770)

14 – Birth of Robert Fulton (1765-1815), inventor of the

steamboat, in rural Pennsylvania.

15 - The Articles of Confederation were adopted by

Continental Congress. (1777)

17 - Elizabeth I crowned Queen of England at the age of 25, “reigning

until 1603 when she was 69. Under her leadership, England became a world power,

defeating the Spanish Armada, and witnessed a golden age of literature

featuring works by William Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser and others.” She defined

the Colonial Era in ways few others have. (1558)

17 - New York Weekly Journal publisher John Peter Zenger is

arrested and charged with libeling the colonial governor of New York, a year

after the newspaper was established. (1734)

17 - The U.S. Congress meets for the first time in the new

capital at Washington, D.C.; and President John Adams becomes the first

occupant of the Executive Mansion, later renamed the White House. (1800)

17 - Birth of German mathematician August Mobius (1790-1868)

in Schulpforte, Germany.

18 - First book in the English language, The Dictes and Sayengis of the Phylosophers,

printed by William Caxton. (1477)

18 – Birth of German composer Carl Maria von Weber

(1786-1826) in Eutin, Germany.

18 – Birth of Photography inventor Louis Daguerre

(1789-1851) in Cormeilles, near Paris. Inventor of the daguerreotype, the first

practical photographic process to produce lasting pictures.

19 - Puerto Rico discovered by Columbus during the second

voyage to the New World. (1493)

19, 1703 – Death of the "Man in the Iron Mask," a

prisoner of Louis XIV in the Bastille in Paris. Speculation abounds on this man’s

identity: was it Count Matthioli, who double-crossed

Louis XIV, or possibly the brother of Louis XIV? (1703)

20 - New Jersey is the first state to ratify the Bill of

Rights. (1789)

21 - The first free balloon flight takes place in Paris as

Jean Francois Pilatre de Rozier and Marquis Francois Laurent d'Arlandes

ascended in a Montgolfier hot air balloon. The flight lasts about 25 minutes

and travels nearly six miles at a height of about 300 feet over Paris. Witnessed

by Benjamin Franklin, among others. (1783)

22 - Portuguese navigator Vasco Da Gama, leading a fleet of

four ships, is the first to sail round the Cape of Good Hope, searching for a

sea route to India. (1497)

22 - Death of Edward Teach, AKA Blackbeard the pirate, off

the coast of North Carolina after a long and prosperous career. (1718)

24 – Birth of Zachary Taylor (1784-1850) 12th U.S. President,

in Orange County, Virginia. Only served as President from March 4, 1849 to July

9, 1850, when he died in the White House from illness.

25 – The last British troops leave New York City at the end

of the Revolutionary War. (1783)

26 – Observance of the first American holiday, proclaimed by

President George Washington to be Thanksgiving Day, a day of prayer and public

thanksgiving in gratitude for the successful establishment of the new American

republic. (1789)

26 - The first lion exhibited in America (1716)

26 – Birth of Harvard College founder John Harvard

(1607-1638) in London.

27 – Birth of Anders Celsius (1701-1744) in Sweden. Inventor

of the centigrade (Celsius) temperature scale commonly used in Europe.

28 - Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan passed through

the strait later named for him, located at the southern tip of South America,

thus crossing from the Atlantic Ocean into the Pacific. (1520)

|

| John Bunyan's magnum opus |

28 - Panama declares independence from Spain and joins the

fledgling nation of Gran Colombia. (1821)

28 – Birth of British artist and poet William Blake (1757-1827)

in London.

28 - Birth of John Bunyan (1628-1688) in Elstow,

Bedfordshire.

30 - The Battle of Narva takes place, where 8,000 Swedish

troops under King Charles XII invade Norway, defeating a force of 50,000

Russians. (1700)

30 - Provisional peace treaty between Great Britain and the

United States is signed, ending America's War of Independence. (The final

treaty was signed in Paris on September 3, 1783.) It declared the U.S.

"...to be free, sovereign and independent states..." and that the

British Crown "...relinquishes all claims to the government, propriety and

territorial rights of the same, and every part thereof." (1782)