|

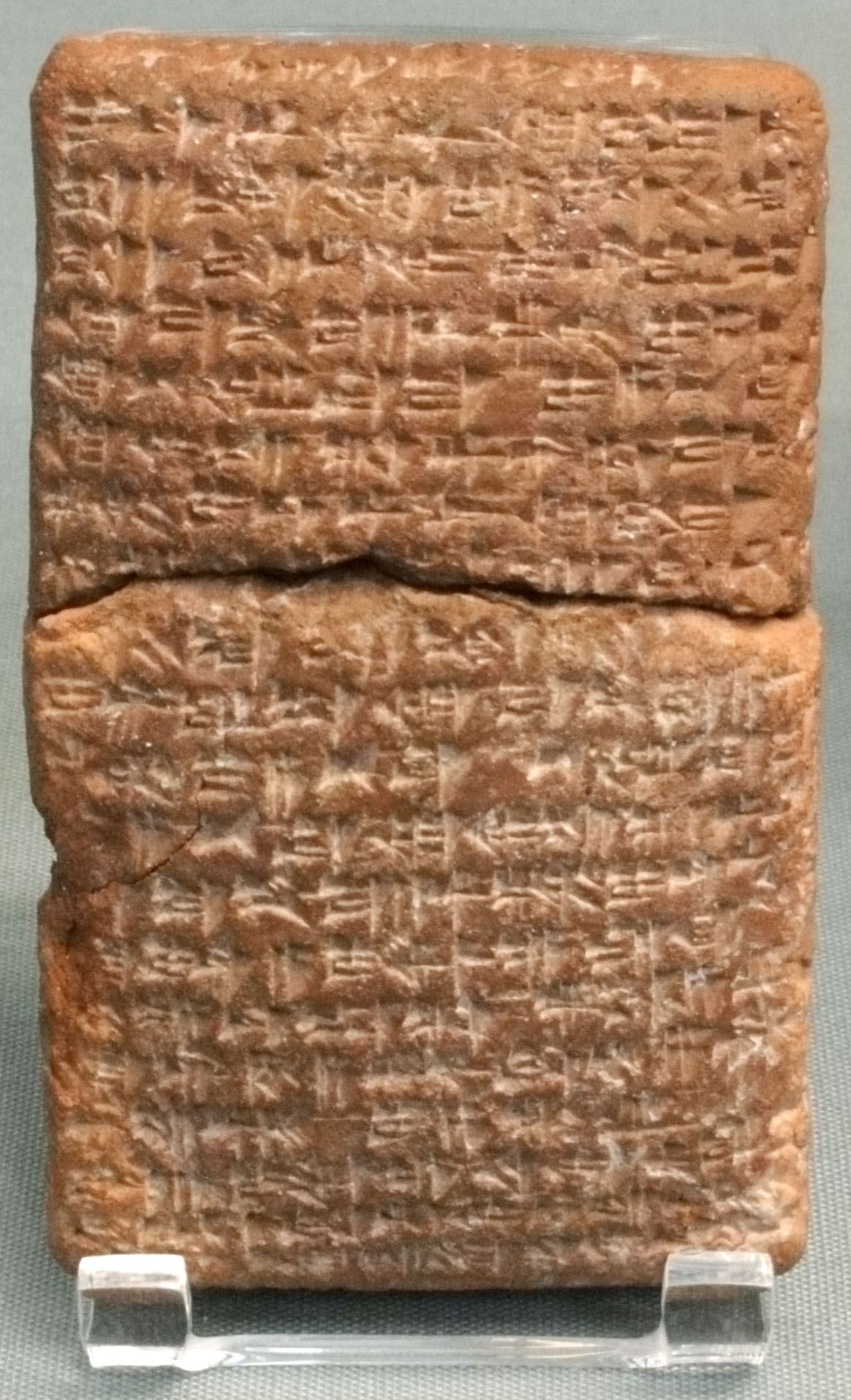

| Fugitive slave treaty from 1480 BC |

In my last post, I discussed the very difficult topic of

slavery, an institution one cannot avoid in any study of our country’s history—indeed,

of serious study of nearly any civilization. Though modern, reductionist

history would blame the evils of chattel slavery (i.e., treating human beings

as moveable property) solely on European colonization, beginning with Christopher

Columbus, the institution existed as a fixture in Sumerian, Babylonian, and

Egyptian cultures, as well as early South American and African societies.

So how does the practice of slavery touch the native peoples

of North America, beyond the obvious influence of Columbus?

First, slavery was definitely practiced between native

tribes, but not so much as an official institution as we understand from, say,

the Civil War era. This excellent summary by author Christina Snyder explains

it better than I could:

The history of American slavery

began long before the first Africans arrived at Jamestown in 1619. Evidence

from archaeology and oral tradition indicates that for hundreds, perhaps

thousands, of years prior, Native Americans had developed their own forms of

bondage. This fact should not be surprising, for most societies throughout

history have practiced slavery. In her cross-cultural and historical research

on comparative captivity, Catherine Cameron found that bondspeople composed 10

percent to 70 percent of the population of most societies, lending credence to

Seymour Drescher’s assertion that “freedom, not slavery, was the peculiar

institution.” If slavery is ubiquitous, however, it is also highly variable.

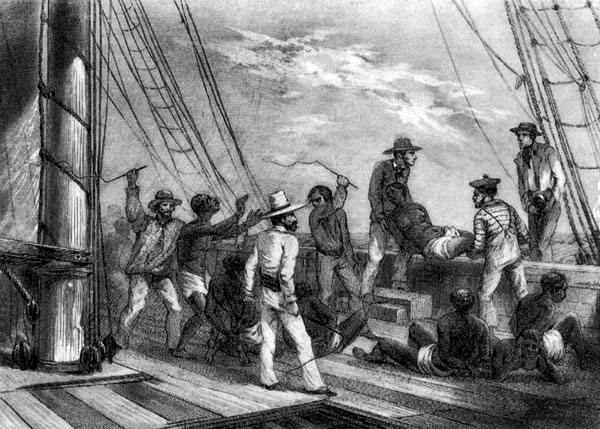

Indigenous American slavery, rooted in

warfare and diplomacy, was flexible, often offering its victims escape through

adoption or intermarriage, and it was divorced from racial ideology, deeming

all foreigners—men, women, and children, of whatever color or nation—potential

slaves. Thus, Europeans did not introduce slavery to North America. Rather,

colonialism brought distinct and evolving notions of bondage into contact with

one another. At times, these slaveries clashed, but they also reinforced and

influenced one another. Colonists, who had a voracious demand for labor and

export commodities, exploited indigenous networks of captive exchange,

producing a massive global commerce in Indian slaves. This began with the second

voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1495 and extended in some parts of the

Americas through the twentieth century. During this period, between 2 and 4

million Indians were enslaved. Elsewhere in the Americas, Indigenous people

adapted Euro-American forms of bondage. In the Southeast, an elite class of

Indians began to hold African Americans in transgenerational slavery and, by

1800, developed plantations that rivaled those of their white neighbors. The

story of Native Americans and slavery is complicated: millions were victims,

some were masters, and the nature of slavery changed over time and varied from

one place to another. A significant and long overlooked aspect of American

history, Indian slavery shaped colonialism, exacerbated Native population losses,

figured prominently in warfare and politics, and influenced Native and colonial

ideas about race and identity. [

Indian Slavery, emphasis mine.]

Early in my study of the colonial era, I received the

impression that the practice of enslaving Native Americans died out as the

African slave trade gained momentum, but there is increasing evidence to the

contrary.

One author’s study reveals

that the slave trade among the Indians of the West was alive and well during

the settlement and annexation of California. He also reveals how the Mormons

found the same upon their arrival in Utah, and how attempts to “rescue” the

victims of slavery only fed racial prejudice within Mormonism.

|

| Cherokee delegation to Washington in 1866 |

A particularly startling aspect of the dynamics of slavery

on native peoples surfaced in connection with the

Cherokee and

Seminoles, both

of which were removed to Oklahoma Territory over the Trail of Tears. Apparently

it was well known and accepted that many wealthy, landholding Cherokee owned

black slaves, and took them along during the removal (see the quote above). Some Seminoles

re-enslaved blacks who escaped to Florida, although it’s reported that their

interpretation of slavery was more “fair” than that practiced to the north.

Time fails me to go deeply into any of these aspects, and I

want to make it clear that as a historian and storyteller, I’m merely making

observations, not offering a defense or pointing fingers in any way. In our own

times, however, we must understand as much of the entire picture as possible.

It is, after all, our mission here at Colonial Quills to educate about

little-known aspects of our chosen span of history.

For more reading:

The Untold History of American Native Slavery (interesting site, with a ton of supporting and related articles)

America's Other Original Sin

... and just for fun,

FACT CHECK: 9 Facts About Slavery