I was raised as a

Mennonite by parents who grew up

Amish, and I have a multitude of Amish relatives. With the continuing interest in this conservative denomination and the popularity of Amish romances, I thought it might be interesting to take a look at the origins of the Amish church in America, especially their main settlement in the mid 1700s, the

Northkill Amish Church, named for the creek that wound through it.

|

| Northkill Marker |

For the past few years I’ve spent considerable time researching the lives of my

Hochstetler ancestors for the novel a cousin, author Bob Hostetler, and I have coauthored, releasing March 1. Titled

Northkill, the story focuses on the family of Jacob Hochstetler, whose farm came under attack during the

French and Indian War. The story of the Hochstetler massacre is well known in the Amish and Mennonite communities, and a plaque marks the site of the farm where it happened, near present-day Shartlesville, Pennsylvania. We were determined to make our fictional depiction of this story as accurate as possible 257 years later, which meant not only doing intensive research, but also mentally, emotionally, and spiritually living in their time. Writing

Northkill has been a fascinating and emotional journey, all the more so because as direct descendents of the story’s main characters we owe our very existence to them.

The Amish came to America because of severe persecution in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries due to their insistence on believers’ baptism and opposition to military service. They were drawn to Pennsylvania by

William Penn’s assurances of religious freedom and economic opportunity denied them in Europe. The Northkill Creek area in Berks County was opened for settlement in 1736, and that year a couple of Amish families settled there, with others following the next year. My great-great-great-great-great grandfather and grandmother, with two small children, were part of a group that landed at Philadelphia on November 9, 1738, aboard the ship

Charming Nancy.

They soon joined other members of their church in the Northkill settlement 75 miles northwest of Philadelphia. Additional groups immigrated to the area in 1742, and again in 1749, when

Bishop Jacob Hertzler arrived to provide leadership for the growing congregation. The earliest known organized Amish church in America, it included nearly 200 families at its height. It remained the largest Amish settlement in America into the 1780s, when it slowly declined as families moved westward in search of better farmland.

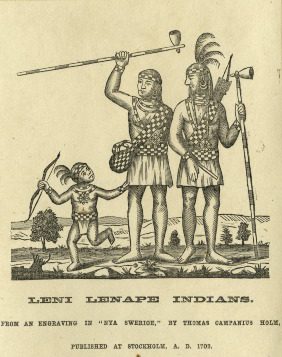

The Northkill settlement lay at the foot of the Blue Mountain, the legal boundary of English settlements according to treaties with the Native Americans. However, white settlers persisted in crossing the mountains into territory claimed by the French and their native allies. Hostilities finally broke out in 1754, with the French enlisting the Indians to attack the border settlements. During the French and Indian War over 200 settlers were killed in Berks County alone. The Indian attack against my ancestors’ farm early on the morning of September 20, 1757, was one of those horrific incidents.

On Monday, September 19, the Hochstetler family hosted an

apfelschnitzen (apple cutting) frolic for the young people of the church. The youth traditionally stayed late into the evening to enjoy games and courting, but their guests finally left and the family went to bed. In the dark hours of Tuesday morning, the oldest son still living at home, Jacob Jr., roused when the family’s dog set up a clamor. When he opened the door, 17-year-old Jacob was shot in the leg by a member of a war party composed of Delaware and Shawnee warriors who surrounded the house.

The family managed to barricade themselves inside. Because the Amish hold fast to the commandment not to kill, Jacob made what must have been a truly wrenching decision that they wouldn’t shoot at their attackers despite the hunting rifles at hand and his sons’ desperate pleas. When the Indians set fire to the house, Jacob, his wife, three sons, and a young daughter were forced to take refuge in the cellar. During the terrifying hours that followed, they repeatedly beat out flaming embers while the house burned above their heads.

|

| Artist's Depiction of Attack on Hochstetler Farm |

At last dawn brightened the sky. Seeing through a narrow window in the foundation that the Indians had withdrawn and believing themselves safe, the family hurriedly forced their way out, barely escaping the flames. But one of the warriors, a young man called Tom Lyons, had lingered in the orchard to pick ripe peaches. When he saw them emerge from the blazing structure, he called the rest of the war party back, and they fell upon their defenseless victims.

The mother, the wounded son, and the young daughter were killed and scalped. Jacob and two sons, Joseph, 15 years old, and Christian, 11, were carried away into captivity. Their journey, described in a remarkable deposition preserved in the papers of British

Colonel Henry Bouquet after Jacob’s dramatic escape, will be the subject of book 2 of the series,

The Return. It will cover the captives’ lives among the Indian clans the French gave them to, Jacob’s harrowing escape and his efforts to find his boys, Joseph and Christian’s forced return home after the war, and their difficulty in assimilating into a culture they had largely forgotten, while reestablishing a relationship with the father whose decision had torn apart their lives.

The story of my ancestors is a deeply moving account of obedience, hope, and endurance, and of God’s unfailing faithfulness to His people even in the worst of trials. In the centuries since the attack, our family has been extraordinarily blessed. Jacob’s descendants have spread throughout the world and their accomplishments span a wide range of endeavors. My ancestors’ example daily inspires me to faithful discipleship, and my hope and prayer is that it will equally inspire readers in their walk with the Lord.

For more information, visit my

Northkill blog.

Pegg Thomas writes "History with a Touch of Humor."

Pegg Thomas writes "History with a Touch of Humor."