By Susan F. Craft

(In honor of my novel, Cassia, which will be released by Lighthouse Publishing of the Carolinas, Heritage Beacon, this coming September, I plan to write my blogs for the rest of the year about PIRATES. Argh!!!)

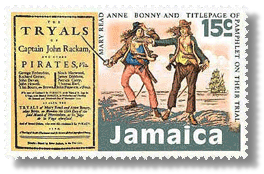

Anne Bonney, born in the late 1660s in County Cork, Ireland, was the illegitimate daughter of William Cormac, a lawyer, and his housemaid. The family immigrated to a plantation in Charleston, SC, where she grew up and eventually eloped with James Bonney, who took her to a pirates’ lair in the Bahamas.

She left Bonney in 1718 to become the mistress of Captain John “Calico Jack” Rackham. She claimed that Bonney had turned informant in order to receive the king’s pardon offered by Bahamian Governor Woodes Rogers. She sailed with the captain on his sloop

Vanity and, dressed as a man, soon became an infamous pirate. She had a child by Rackman and retired from piracy long enough to deliver the baby. She left her infant son with friends in Cuba and returned to piracy.

Mary Read, born about 1690 in Plymouth, England, was the illegitimate daughter of a woman whose seaman husband left on a long voyage and was never heard from again. When their money ran out, Mary’s mother took her to London to ask her mother-in-law for help.

The woman didn’t like girls, so Mary’s mother dressed Mary as a boy and made her pretend to be her son. Mary masqueraded as a boy for many years, even after the woman died. After working as a footboy to a French woman, she enlisted as a male in a foot regiment in Flanders and later in a horse regiment, serving with distinction.

Giving up her double life, she fell in love with and married a fellow soldier, and they became innkeepers of the

Three Horseshoes in Holland. Her husband died young, and when Mary’s finances dwindled, she reverted back to men’s clothing and went to sea on a Dutch merchant ship. English pirates commandeered the ship that eventually was overtaken by Captain Rackman.

Anne and Mary discovered each other’s cross-dressing secret and became close friends. Mary fought in a duel to protect her fiancé, killing her opponent. They became known as ruthless and bloodthirsty “fierce hell cats,” with violent tempers.

In late October 1720, Rackman's ship was attached by a British Navy sloop. The drunken male pirates quickly hid below deck, leaving Anne and Mary to defend their ship, but they were soon overwhelmed, and the entire crew was captured and taken to Jamaica for trial.

Captain Jack and the male members of his crew were tried on November 16, 1720, and sentenced to hang. Anne and Mary were tried one week after Rackham’s death and were also found guilty. But at their sentencing, when asked by the judge if they had anything to say, they replied, “Mi’lord, we plead our bellies.” Both were pregnant.

British law forbade killing an unborn child, so their sentences were temporarily stayed.

Some say Mary died of a fever in prison before the birth of her child. Other reports say she escaped.

There is no record of Anne’s execution. Some reports say her wealthy father bought her release after the birth of her child, and she settled down to a quiet family life on a small Caribbean island. Others believe she lived out her life in the south of England as a tavern owner and entertained the locals with tales of her exploits.

Susan F. Craft is the author of a SIBA award-winning Revolutionary War suspense, The Chamomile, and its sequel Laurel. The third novel in this trilogy, Cassia, will be released this September.

Susan F. Craft is the author of a SIBA award-winning Revolutionary War suspense, The Chamomile, and its sequel Laurel. The third novel in this trilogy, Cassia, will be released this September.