These are the words and hand of John White, appointed first as professional artist and mapmaker to three separate voyages to the New World.

It has been commented that White not only portrayed the indigenous peoples of the New World with a realism uncharacteristic of the era, but with sensitivity and grace.

Don't you just love the face of the baby peeking out of his (her?) mother's hood?

In 1584 and 1585, White accompanied two other expeditions, both to Virginia. His map of the coast was remarkably accurate, by modern standards:

Dozens of his watercolor sketches also survive of various flora and fauna, presumably of England as well as the New World. The man had an amazing eye for detail, and the patience to reproduce it for the world to see.

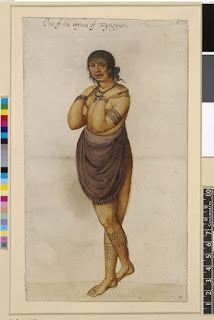

Once again, however, it's his portraits of the people of the New World--of what would become North Carolina, here--that I find most arresting. Charged with "painting to life" the land and peoples, he did so, capturing faces and scenes from the Caribbean up through Florida as well as the dress and manners of the Carolina Algonquin peoples. In so doing, he provides the only view we have of this time and region.

He sketches and paints with so much realism, in fact, that it's somewhat problematic for modern sensibilities. This Algonquin woman, identified by White as "one of the wyves of Wyngyno," a weroance or chief of Secotan, stands in a pose that every woman ever will easily recognize. Thomas Harriot, a prominent scientist and mathematician who worked alongside White during the 1585 expedition, described it as "maydenlike modestye." Indigenous manner of dress accommodates the bare essentials of modesty, at least in summertime, but only barely. I can imagine what they must have thought of the English with their many layers! We know from their writings that the English regarded them to varying degrees as very much lesser peoples.

Interestingly, though, some--Harriot included--felt the Algonquin peoples had much to teach the English, not the least of all that they ate much more healthfully and without the excess the English were prone to. In his written account, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, first published in 1590 with woodcut prints of White's sketches, Harriot commented that the only area where they seemed deficient was their understanding of spiritual things, and told of his efforts to explain to them the basics of Christianity. He also speaks in scathing terms of those who went to the New World only to look for gold and silver and cared for nothing else, or who were of delicate upbringing and could not handle the primitive conditions of the New World.

For those who read my last post on our visit to Roanoke Island Festival Park, these next two prints illustrate what the park attempts to bring to life in their Algonquin life displays:

"The broyling of their fish over the flame of fier"

The complaint is made that Harriot's writings, and White's work as well, was only carried out with an eye to the economic feasibility of supporting an English colony in the New World, but both men could be credited with seeing the Algonquins as a people in their own right and worthy of respect and dignity, even when others did not.

For John White, this respect served him well as Governor of Virginia, however short-lived was his time there in 1587. We know from his own account how grieved he was to leave, and how intensely he desired his colonists to live with love and friendship with the Croatoan people and their neighbors.

For further study:

All images © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-