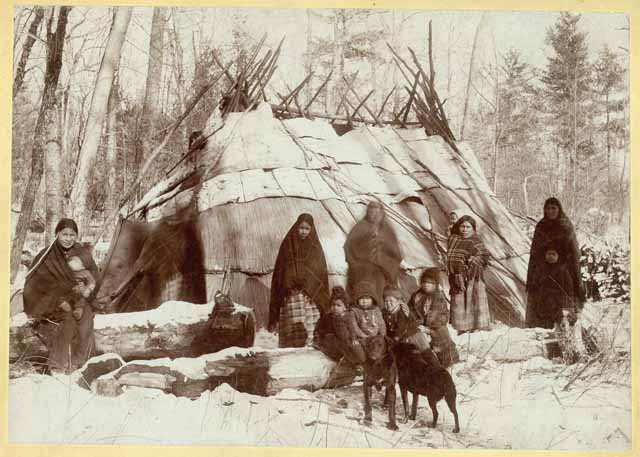

The Native Americans were very diverse in their survival means. I live in Northern Michigan and most of the tribes native to this area headed away from the lake to their inland winter camps, most of them farther south in the state. They built winter lodges of birch bark that were up to twenty feet long and ten feet wide. As many as three generations of a family would live in the lodge all winter. Typically there would be a firepit at each end, one to cook over and one for warmth.

The Native Americans in this area were farmers. They collected the wild rice in season, but also cultivated and grew corn, beans, squash, and other vegetables they stored for winter survival. These weren't small patches, but acres of fields tended by the women all summer long. It was enough - at least in the good years - to see them through the winter.

Keeping warm was a full-time occupation. They coated their skin with bear and goose grease. This both repelled moisture and retained heat. They also wore animal skins tanned with the fur on, but unlike fur coats of today, they wore them with the fur against their skin for added insulation and warmth. Huge blankets were made of rabbit skins sewn together and used to cover several people, thus keeping in more body heat on cold nights.

As well as keeping warm, they needed to keep busy. During the summers they were tending their crops, gathering wild edibles, hunting, and fishing. During the winters, men still hunted, fished through the ice, and trapped animals for their warmest furs. The women did the handwork needed for the next summer, including making clothing and decorating it, making baskets, carving bowls, and - of course - tending to the children.

It wasn't an easy existence. It makes me appreciate my snug house with its wood heat and insulated windows.

Pegg Thomas writes "History with a Touch of Humor."

Pegg Thomas writes "History with a Touch of Humor."