"Never such a Snow, in the Memory of Man!"~ Rev. Cotton Mather, March 7, 1717

|

| Spencer-Peirce-Little House, c. 1690, Newbury, Massachusetts Photo courtesy: Karen Lynch |

In 1717, my ancestor’s home in Newbury, Massachusetts was covered in snow up to the second floor. Last year, our Elaine Cooper wrote about this drastic winter in her post: The Great (and Terrible) Snowstorms of 1717. This winter is also going down as a record-breaker in New England with seven feet of snow falling in Boston in a matter of weeks. In my own state of Maine we have had at least six. The roads have been so full of snow that the plows are challenged to find a place to put it all. After each storm, our road becomes more and more narrow with snow banks rising higher and higher. But in the early days of our country, snow falls created a different type of challenge than we experience today.

|

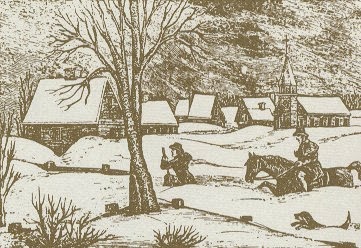

| "Great Snow in 1717" wood cut. |

The East Coast settlements endured such harsh winters that much of the initial populations were tragically reduced in their struggle to survive. The food supplies were limited, shelter insufficient, and illness ran rampant. In fact, in 1608, a new colony in Popham, Maine nearly succumbed to the "vehement" winter and those few that survived returned to England.

|

| Painting of Colonial Jamestown by Sidney King, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park. |

According to weather historian David Ludlum, author of Early American Winters, 1604-1820 snows continued into April and even into May during colonial days. Extended winters and great cold meant reduced deer populations and starving cattle, later growing seasons, limited resources of firewood, reduced food stores and hardship in obtaining supplies, restricted transportation and communication, etc..

In Snow in the Cities: A History of America's Urban Response by Blake McKelvey a chapter devoted to "Snow in Pedestrian Towns from 1620-1800" provides some interesting detail about how towns managed their snow issues in early times. Although there were no automobiles, snow drifts needed to be leveled for sleighs to break through and pathways needed to be shoveled. In some cities, sleighs were required to have bells to warn pedestrians of their approach. By the early 1800s cities instituted ordinances for residents to assist with snow removal to keep up with increasing numbers of travelers and their conveyances. Ships were caught in the harbor and shipments were halted during winter months, in fact, Boston Harbor froze for 30 days in 1740. But while ferries and boats were frozen ashore, wagons could be drawn across ice laden rivers, which must have proved advantageous. Some folks traveled by snow shoes which would have been obtained through trade with the Indians.

|

| Driving the Carter Coach in a snow storm at Colonial Williamsburg. Photo by David M. Doody |

Colonial Americans may also have enjoyed some type of winter recreation, but primarily they would have been about their daily duties, especially though performed by the hearth. Ice skating was an activity brought from England that they participated in. Skiing was not brought to America until the 19th century from Scandinavian immigrants, so skiing would not have been a pastime. Children also have enjoyed sledding and building snow forts and leisurely sleigh rides may have been enjoyed by all. But most certainly great care would have been given as snow in those times could be a perilous thing.