Studying North America in the 1600s is to learn of the great explorers and the claiming of land for European empires, as well as the founding of colonies across the landscape. One such explorer was Daniel Greysolon Sieur du Lhut (or in the Quebec archival rendering: Daniel de Gresolon du Luth and Americanized as Daniel Greysolon Duluth). In late June, 1679, he planted a banner for France, "His Majesty's Arms" on the location of present day Duluth Minnesota, at the very head of Lake Superior, "in the great village of the Nadouecioux (Sioux), called Izatys, where never had a Frenchman been..." That was what Duluth penned in a letter to the French Minister of Marine, to quell allegations made against him that he had deserted Montreal to engage in the fur trade without the proper licensing to do so. He was not quite accurate in his proclamation that no other Frenchman had been in this part of the world. Groseilliers and Radison had arrived in Sioux country some years prior. However, I digress.

Let's back up.

Duluth was born in Saint-Germaine-en-Laye near Paris in or around 1654. At that time, Saint Germaine was something of a resort area for the French court. Duluth's own family had some noble lineage along with a degree of wealth from his mother's side which qualified him as a "gentleman". Being among the "petit noblesse" (similar to being a gentleman of lower lineage in England) he decided to join the army.

Now fast-forward a little bit.

Duluth served as a "Gendarme de la Guard du roi", military guardsmen who were only recruited from among the nobility. He boasted about this appointment for years to come, even though he eventually found the slow advancement and days spent around a somewhat effeminate court life unsatisfactory for a young man of his energetic and ambitious nature. Rather, life in New France sounded exciting. He resigned from his position with the Guard and soon made his way to Montreal where friends and family, as well as his previous commission, gave him ready entry into Montreal society. In those esteemed circles he met the old Boucher family, who had several daughters, one in particular who caught his eye and then his heart.

Within a year or two, however, Duluth had to return to France to settle some family matters. While he was there, he became caught up in the Franco-Dutch war and took part in the bloody battle of Seneffe, serving as a squire to the young Marquis de Lassay.

Finally, at war's end, he returned again to Canada and leased a small home. His amore for Madamoiselle Boucher had not lessened during his time away, and a year or two later he built a much more elegant and somewhat palatial estate on the shores of the majestic St. Lawrence River. He no doubt hoped to bring his lady-love to his expansive, well-appointed home as his bride. In the meantime, he also developed aspirations to trade in the growing fur market.

Meanwhile, the Bouchers had risen to even higher prominence in Montreal society. With their advancement in social circles, the young lady in question, for whom Duluth had long pined, disapproved of his plans to enter trade. The couple's differing opinions rose to surface in quarrels again and again, apparently heatedly at times. Caught in this stalemate, it eventually became clear to Duluth that he had lost at love, so the two parted company. Duluth then did what any lovelorn, heart-broken individual might do. He got out of there.

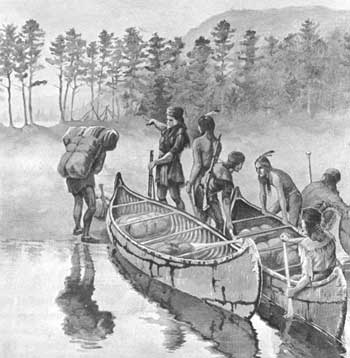

Being still a man in his twenties, the call of the Far West beckoned. Duluth quickly sold his fine home and invested his money in everything he would need to venture west, from canoes to trade goods. He also worked at cultivating friendly relations with the natives, and as a result, they offered him three slaves as guides for his journey. With his guides and eight Frenchman, including his brother Claude, the brigade embarked westward, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Duluth spent the following winter at the Falls of Saint Mary's (the Sault), an important village set neatly on the Saint Mary River connecting lakes Superior and Huron. During that time, Duluth's head probably cleared some after his heartbreak, for he seemed to recall that he'd departed Montreal without a proper license to trade from Governor Frontenac. In an attempt to set things right, he wrote the afformentioned letter, assuring the French Minister of his loyalties to France and of his intent to open up the west in such a way meant to expand the King's interests. He pointed out his purpose to bring peace between the Sioux and Ojibwe, and to secure the natives' trade away from the English by currying their favor so that they might promise to bring all their pelts to Montreal and Quebec.

It seems that Duluth all along did intend to reach the mouth of the St. Louis River at the head of Lake Superior, and once he did, he crossed what was called the "Little Portage" and planted His Majesty's colors, laying all claim to the region south and west of Lake Superior for France.

Duluth went on to meet with the Indians, spreading feasts, summoning councils, and doing all in his power to show good will and establish firm relations. He ventured deep into the northern forests and down the rivers to the south all the way to the Mississippi. Far and above his own interests in fur trading, he was patriotic. Many more adventures came his way, although it appears he never again sought to take a French wife. He died in in Montreal in 1720 with his valet LaRoche in attendance to the end.

My belief is that once burned was all it took for monsieur Duluth to give up matrimonial notions. He had more illustrious endeavors to attend to for his true mistress--France. That's my theory, and I'm sticking to it. I'll share a bit more about Daniel Greysolon Sieur du Lhut next month, when I write about the infamous scourge of fur traders known as the courier du bois.

Until then, here's to love and adventure.

Naomi Musch

|

| Stone marker near the site where Daniel Greysolon Sieur du Luth landed and planted the French flag in present Canal Park, Duluth, Minnesota. |

I had no idea, but then again, I know so little about him. This likely has to do with locale, and the sad face even history nerds have to pick and choose their subjects!

ReplyDeleteThanks Naomi! Very interesting!

It's always interesting to look into the history of individual sections of the country. You just never know what you'll find.

ReplyDelete