A Vote and a Voice by Carla Olson Gade

|

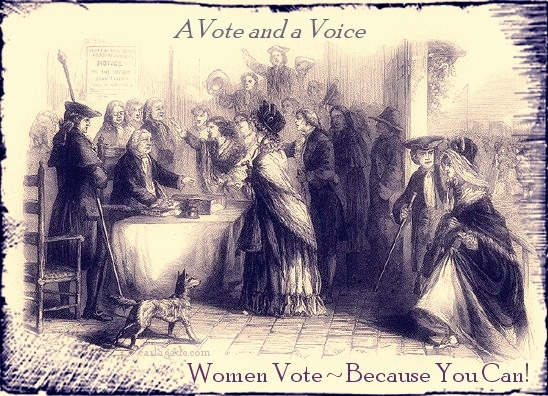

| Photo of colonial elections from history.org. |

"If I cannot be a voter upon this occasion I

will be a writer of votes.

I can do something in that way.” ~ Abigail Adams

I can do something in that way.” ~ Abigail Adams

In Colonial America, the right

to vote was given to property owning male adults. When a man cast a vote in any sort of election, the vote was cast on behalf of his family. Under the English common law

doctrine of coverture, the husband covered his wife’s legal identity under the

authority of their marriage. William Blackstone’s

Commentaries on English Law (1765-69) describes it as such:

"By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in the law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs every thing."

Husband and wife were considered

"one person at law", with most interests governed by the husband. This

was not necessarily a burden for most colonial women, however, although the concept is astounding to most of our current generation. And some wives did

maintain a degree of financial independence from their husbands through dowries

and pre-nuptual agreements. Yet, if the family had no males who could cast a vote, or

the husband was indisposed at the time of the election, the wife, or most

important woman of the household could vote, such that the family was still

represented.

Though a married woman, or feme covert, was a dependent her

husband in most legal matters, a feme

sole, an unmarried woman, could own property,

enter into contracts and sue or be sued.

"Came Mrs Margaret Brent and requested to have vote in the howse for herselfe and voyce allso for that att the last Court 3d Jan: it was ordered that the said Mrs Brent was to be lookd uppon and received as his Lps Attorney. The Govr denyed that the sd Mrs Brent should have any vote in the howse And the sd Mrs Brent protested agst all proceedings in this pnt Assembly unlesse shee may have vote as aforesd." (Note: Mrs./Mistress was used interchangeably for married and unmarried women until the second half of the 17th century.)

Margaret Brent exclaimed, "taxation without representation is tyranny." And here you thought colonial lawyer, James Otis, Jr. was the first to say that in 1765.

In 1655, Lady Deborah

Moody cast a vote in New Netherlands (later, New York) in a colony-wide election. The widow Moody, a Quaker, had a land grant in her own name and frequently consulted by the governor for nominations to various civil offices.

1701 Albany, New York, a jury of

men and women first heard criminal and civil cases. And a woman had a right to

vote as long as a man permitted it. By the end of the 17th century, women who owned

property in their own names were given permission to vote in Massachusetts. In 1756, Lydia Taft, a wealthy Massachusetts widow, was allowed to vote in town meetings on at least three

occasions in her town of Uxbridge. In In 1724 Vermont included the

names of women land-owners on its polling lists. Women's names appeared on the polling lists in Massachusetts and Connecticut as late as 1775.

At the time of the American

Revolution each colony drafted its own state constitution. While the country won

her independence, women did not. Most states incorporated

language that excluded women from having the right to vote. Various phrases

were used issuing the vote to “freemen”, “free white men”, “male person”, and “man”.

By 1777 women lost the right to vote in New York, by 1780 in Massachusetts, and

by 1784 in New Hampshire. The United States Constitutional Convention of 1787

placed voting qualifications in the hands of each state. In 1776, New Jersey

gave the right to vote to "all inhabitants of this colony, of full

age, who are worth fifty pounds. . .and have resided within the county. . .for

twelve months." Thus, large numbers of New Jersey women regularly

participated in elections and spoke out on political issues.

|

| "Women at the Polls in New Jersey in the Good Old Times." – Howard Pyle |

Late in the 1780’s the

two politcal party systems developed and the Federalist and Republican parties

began courting New Jersey women for their votes. “Whole wagon loads of the ‘privileged fair” were

brought in to cast their ballots. Amidst party conflicts, members charged their

opponents with coaching the women about their choice of candidates, physically

coercing them into voting, and even taking sexual advantage of the women whom

they brought to the polls. By 1807 there was in actuality a voter fraud problem,

and the Democratic-Republicans seized the opportunity to silence the women’s

vote. The vote was rescinded, but for five Presidential elections, women had their

vote.

Women still had a

voice and their sphere of influence was not without its

political reach. Women had to work hard to help maintain the household status,

supporting political ideals in many ways through society events, political

rallies, through industry and boycotts, and even through the transfer of

property.

Marrying a women of property was one means that a man could gain the qualifications to vote if he did not have the necessary property requirements on his own. In 1755, a Thomas Roberts of Virginia, voted “by virtue of his interest” in his wife’s property. Historians have learned that some women intentionally provided male family members with land to enable them to vote. In some parts of Virginia as much as 1/5 of the electorate owed their ability to meet election requirements due to property transfers made to them by women. Anne Holden granted deeds to her male relatives in 1787.

“In consideration of the Natural Love and affection which she bears to John, Francis and Joseph Boggs aforesaid and that they will always Vote at the Annual Election for the most Wise and Discreet men and who have proved themselves real friends to American Independence to represent the County of Accomack, the Receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged.”

If only John Adams

heeded the advice of his wife Abigail when she charged him on the eve of

American Independence to,

"Remember the Ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember, all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies, we are determined to foment a Rebellion and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice or Representation."There was truth in what she said, for it was not until 1848 at the Seneca Falls Women’s Convention that women wrote their own Declaration of Independence. Women rallied on and in 1920 the states ratified the 19th amendment and women were at last given the right to vote.

“Thus has the Love of Liberty and dread of Tyranny, kindled in the Breast of old and young, a glorious Flame, which will eminently distinguish the fair Sex of the present Time through far distant Ages.” ~ Unkown

Female Suffrage, New Jersey

Women in Early America

Colonial Elections

A lot of good information here!

ReplyDeleteWhat a great article, and the graphics are stellar! I want to share that last one on my facebook page :) Thanks, Carla.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Margo and Kathy. And share away!

ReplyDeleteYay Abigail! Very interesting lesson in the history of women's right to vote! Thank you, Carla!

ReplyDeleteGreat research, Carla, and presented in an interesting and fun post. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteTruly amazing and new information for me. Eye opening. I never knew! Women's history has been so neglected. Thank you so much, Carla.

ReplyDeleteWow, great post! The changes in history are so amazing. I, too, wish to share that last photo! Have a great weekend!

ReplyDeleteSometimes I get duplicate copies of political flyers in my household and I think, that's a waste of money. When I got my mail today and looked at the addresses, one to my husband and one to me as individual voters in my household, I was thankful!

ReplyDeleteAll women have only had the right to vote for 92 years in our country. So hard to believe that some women were entitled to vote, but then it was revoked!

ReplyDeleteWe've come a long way! I wonder what the ratio of men to women voters is today.

ReplyDeleteAs usual, you have shared some great history information with us. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteGreat post. I didn't know any of this history before the mid 1800s.

ReplyDeleteGreat question, Chaplain Debbie! Statistics tell us that more women vote than men. Perhaps because we had to earn the right!

ReplyDeleteMen took women for granted back then and take voting for granted now. Women fought for equality back then and take voting very serious now. :)

DeleteJust an awesome post, Carla. I'm late in getting here to read it but so glad I did. I learned a lot. Makes me wonder how women's rights and the voting issue would have evolved, or resolved, and how much sooner, had that generation not rebelled and caused so many state laws to be rewritten in the 1770s and 80s.

ReplyDeleteThat's so true, Lori. Things could be very different now. The push for feminism might not have been so extreme if women's rights were respected earlier on. IMO

Delete